ARTAM MÜZAYEDE (AUCTION HOUSE)

Ottoman Jewels with 2,500 documents and visual materials

5 November 2022

About ARTAM Antik A.Ş.

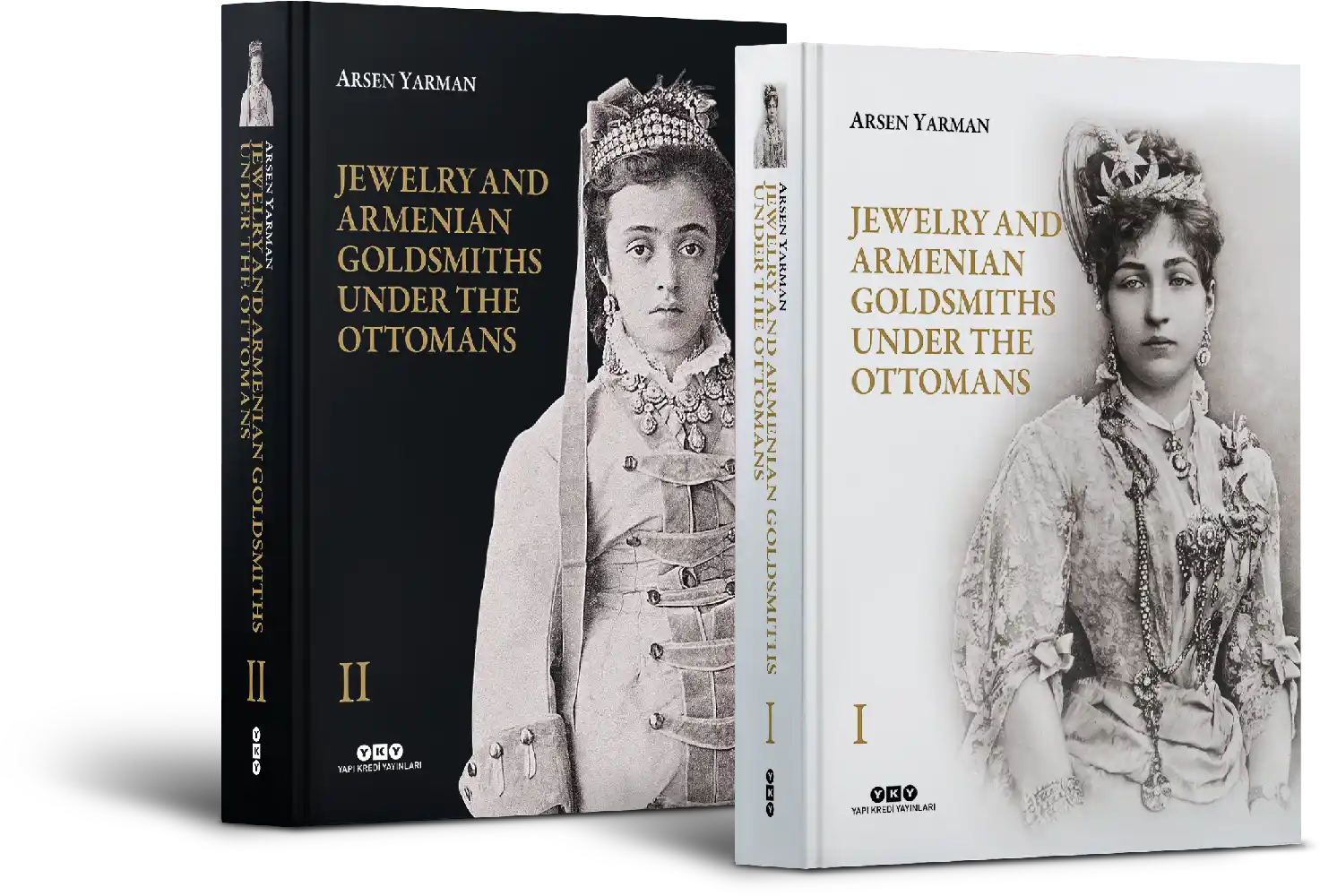

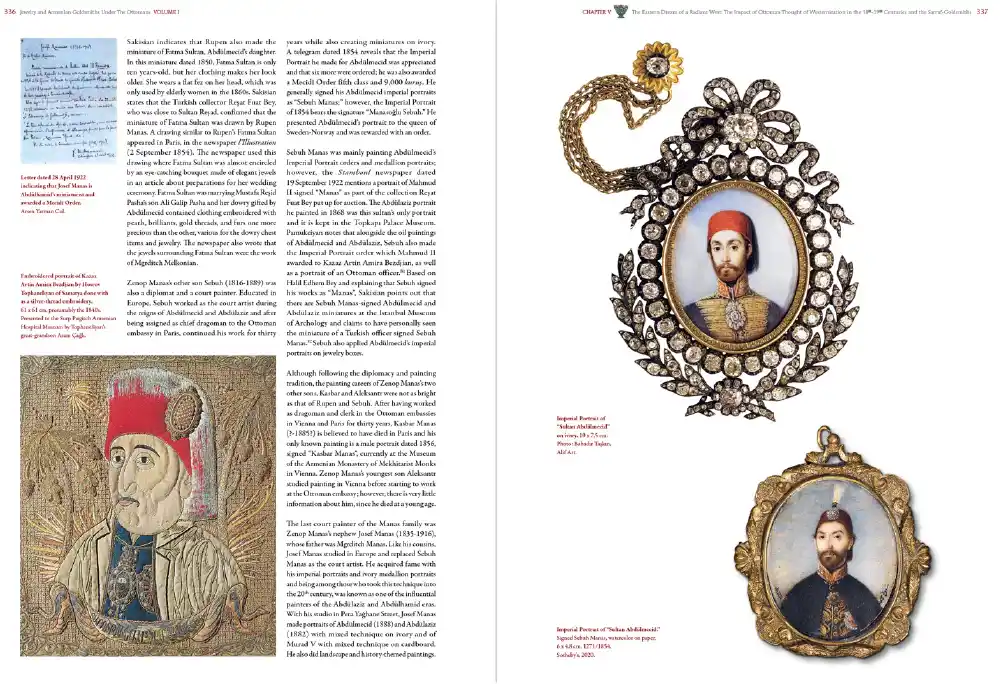

Arsen Yarman

Known for his studies on city and institutional history, the new book by Arsen Yarman, a writer and researcher, focusing on the history of jewelry, which has been seen as a symbol of magnificence and wealth throughout the ages, during the Ottoman period and the contributions of Armenian jewelers to this field, was published by Yapı Kredi Publications. The study titled “Jewelry and Armenian Jewelers in the Ottoman Period” draws attention with its rich visual material on jewelry works. The two-volume study stands out by covering a long period from the 14th century to the 20th century, and thanks to the richness of the archives and sources it uses, it sheds light on the long path that precious gems such as diamonds and gold followed through the hands of money changers and jewelers to the Ottoman palace and the mansions of the rich.

The book, which examines Ottoman jewelry and goldsmithing in a historical context, integrates Ottoman archive documents and visual materials. In this way, the study, which makes it possible to observe the important role played by the Armenians in the formation of the Ottoman’s unique jewelry-goldsmith style through archive documents, and to examine in detail the conditions under which the goldsmith craft was practiced.

A pair of emerald earrings.

Early 18th century. The circular central rosette on both earrings is decorated with a relatively large diamond surrounded by smaller ones and seven faceted and drooping emeralds are attached to the rosette. Photo: Bahadır Taşkın, TSM. 2/7532.

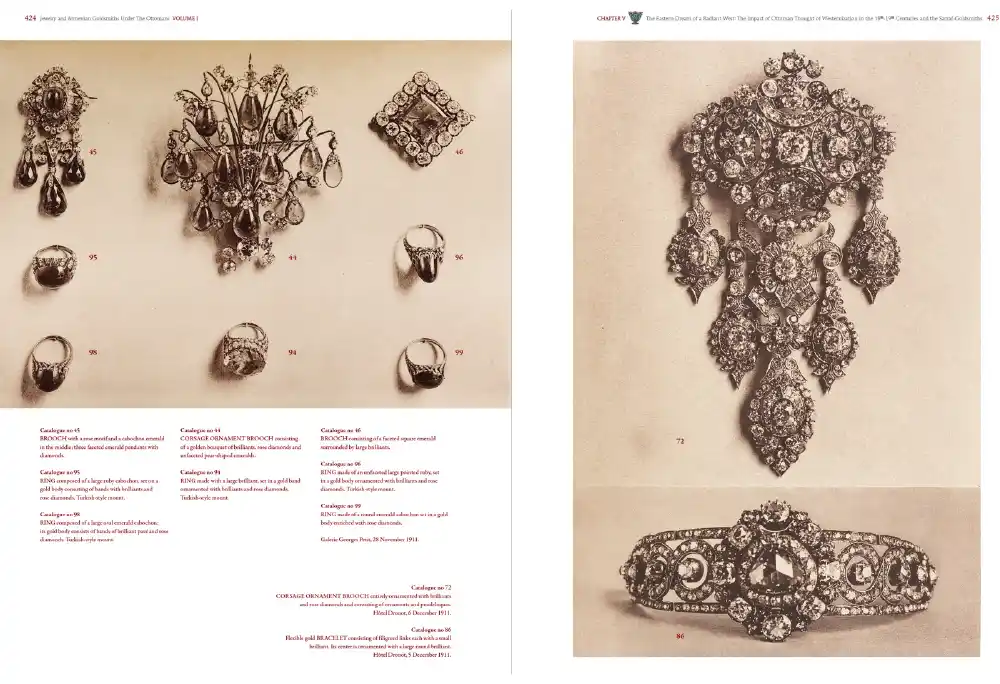

Brooch.

Gold, diamonds, enamel, composite, rock crystal (fine stones). Thickness: 2.3 cm, width: 6 cm, length: 10.6 cm, weight: 0.038 kg. Photo: Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Claire Tabbagh/Collections Numériques, Inv. MAO 931.

‘With this book, I tried to examine issues such as where the gem was located, where the mineral was processed, who designed the jewelry and where, who implemented these designs, and who wore that jewelry in or outside the palace,’ says Yarman about the work he produced following a long process.

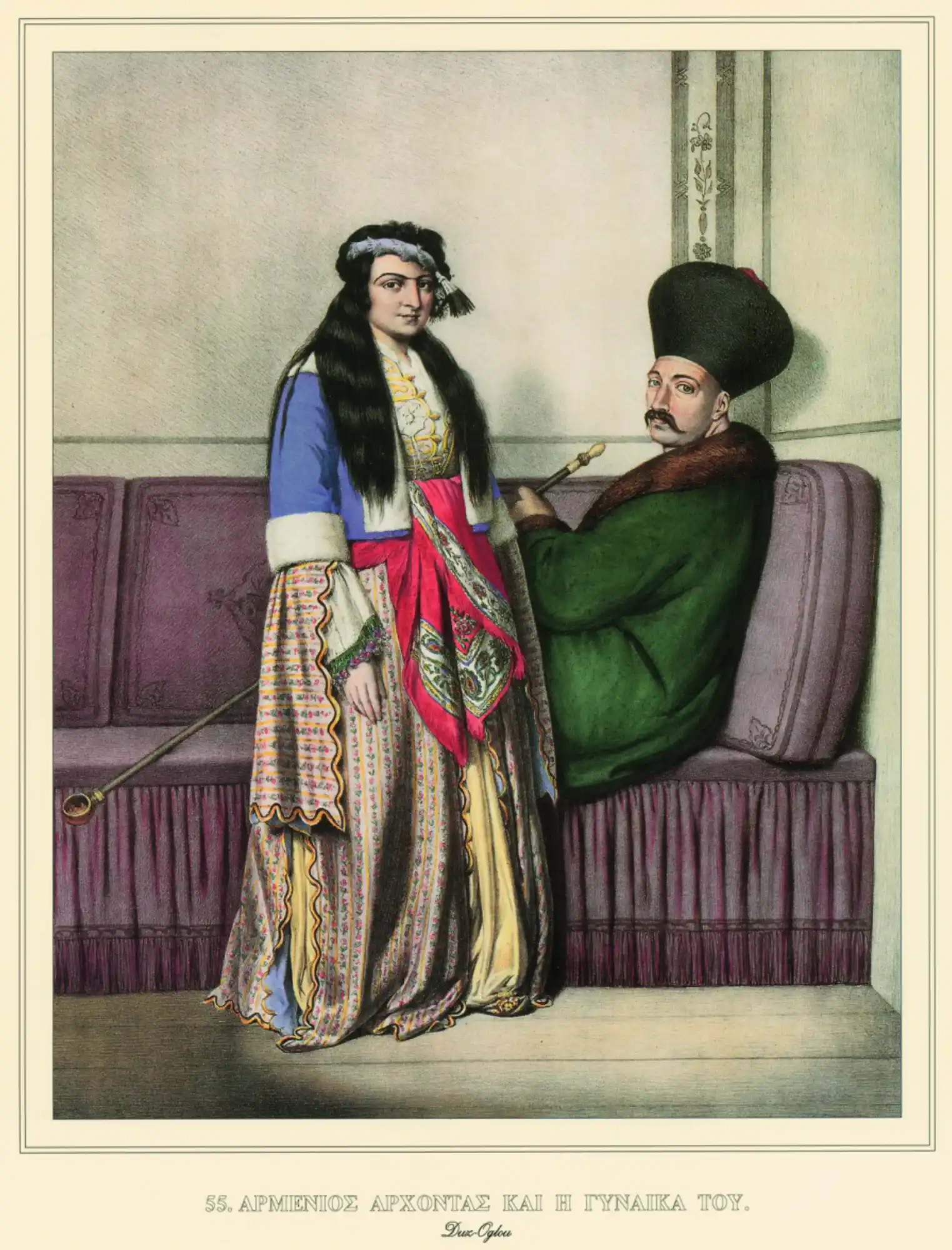

AMİRA SARKİS ÇELEBİ DÜZ AND HIS WIFE.

Yarman, underlines that the personal interest of sultans such as Selim I and Suleiman I in this craft also played a role in the development of Ottoman goldsmithing and states that Suleiman the Magnificent brought many Armenian craftsmen from Van and the surrounding cities to Istanbul during his Iraq campaign. Names such as Hoca Mercan, who worked in the Ehl-i Hiref-i Hâssa Organization [Community of Palace Craftsmen] during this period, Armenian jeweler Yonoz (?) bin Tanrıvirmiş, whose name is mentioned in the Istanbul Kadı Registers from Suleiman’s period, jeweler Maksud Ali, jeweler Mircan, and jeweler Murad, who presented a gift to Kanuni on the occasion of a festival, indicate the presence of Armenian jewelers in early Ottoman goldsmithing. While he does not give a precise date, Evliya Çelebi lists an Armenian Bedros as the most valuable artisan among the jewellery craftsmen (Esnâf-ı Zergerân-ı Cevahirciyân) and that fact shows that it continued like that. Armenian jewelers, who developed their businesses during the reigns of the following sultans, produced a wide range of jewelry, comprising both jewelry and everyday items such as aigrettes, chaplets, crowns, quivers, brooches, belts, bracelets, rings, fans, harnesses, badges, medals, rose water flasks, censers, candlesticks, sugar bowls, cup holders, scepters, mirror frames, cigarette cases, and cradles, whose many examples of which are shown in the book.

Rare Ottoman tiara of gold set with brilliants, diamonds and rubies, thought to be the product of the mint under Duzian.

Height 9.5 cm, diameter 17.2 cm, circa 1800. On the top of the crown there is a floral patterns set with cut diamonds, a large flower with extending leaves and a crescent and star in the center. Both sides of the crown have floral embellishments. Farjam Foundation, Sotheby’s, 2018.

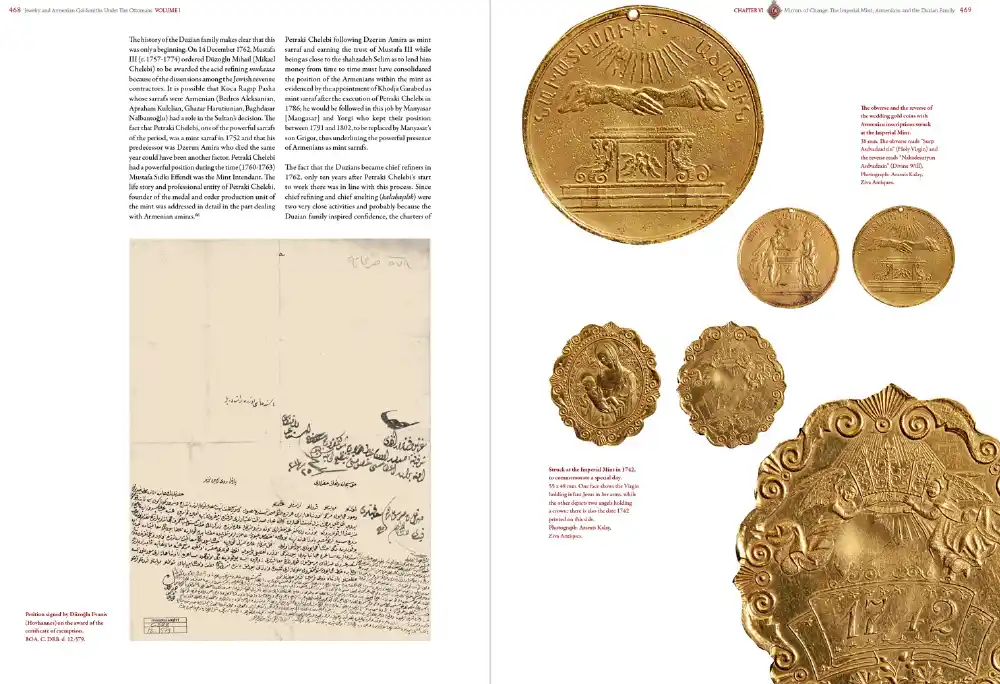

The book also gives extensive coverage to the Düzyans, one of the most important Armenian jewellery families of the Ottoman period. The Düzyans stand out both for their activities at the Mint and for their work for the Ottoman court from the reign of Ahmed III onwards. The family, in the precious stones trade as well as jewelry making, to their craftsmanship and familiarity with foreign jewellery styles, either personally made or supervised the production of many gifts commissioned by the Ottoman sultans for foreign dignitaries. These included the jeweled aigrettes and enameled boxes with tughras presented to Napoleon by Abdürrahim Muhib Efendi; the necklace made for the Empress Eugénie of France; the diamond-studded rapiers and swords presented to King George III of Great Britain and his sons; the gifts given to Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert; the jeweled aigrette sent by Selim III to the Tsar of Russia; the Medjidie Order presented by Abdülmecid to the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph and the diamond necklace he presented to his wife, Empress Elisabeth; the jewelry box given to Napoleon Bonaparte’s ambassador Horace Sebastiani; and the jeweled medals given to the Russian ambassador represent some of the Düzyan family’s work.

The order of Charity made by Ekmekdjian Brothers in its case signed “Ekmekdjian Brothers/Ekmekdjian Frères.”

Photo: Aramis Kalay, Metin Bakır Col.

In his book, Arsen Yarman incorporates and describes places such as the Grand Bazaar, which was important both for the practice of this craft and for the display and sale of the goods produced in the Ottoman period. The book includes information on the architectural integrity of the Grand Bazaar and the workshops and shops located there, it is also possible to find information about the workshops and shops where the jewelry design was done and the rules regarding the functioning of the guild order. Yarman, points out that jewelry is not limited to the production of jewelry and ornaments, but is also used to afford more character and value to objects used in various areas of daily life, and he provides detailed information about watchmaking and weapon making embellished with jewelry. Known as the renowned masters of their time, masters such as the Babayans, Kapamaciyans, Nişastaciyans and Arabyans created the most brilliant products of watchmaking, that developed in the Ottoman Empire, especially in parallel with the increasing cultural-artistic relations established with the West. Levon Mazlumyan, one of the important names of the late Ottoman and early Republican periods, is also considered among the prominent masters, especially in the field of table clocks. As a versatile jeweler, whose career extended into the 20th century after the declaration of the Republic, the most striking of Levon Mazlumyan’s works was the monumental plaque commissioned by the Turkish Grand National Assembly to be gifted to Mustafa Kemal Pasha on the occasion of the transition to the Latin alphabet.

Hand fan.

Late 18th century. The fan mount is made of white goose feather and the lower feathers in the cardboard part are dyed. The plaque on both sides fixing the layers is made of gold. The twisting branches and floral patterns made of large diamonds on both sides indicate that the fan was used double-sided. The center of the ornaments features a large chrysolite, as often seen in Ottoman art. The curvy stem is made of gold and holds a diamond on its end. Photo: Bahadır Taşkın, TSM. 2/3598.

Diamond studded cigarette case.

18-carat gold, 204 gr. 8.5 x 11 cm. Abdülhamid II’s tughra applied on the lid surrounded by diamonds and old-cut stones. Photo: Teoman Mat, Y. B. Col.

Ottoman-style tiara.

Nineteenth century, height 7.9 cm, diameter: 16.1 cm. Gold, diamonds, emeralds and rubies. A peacock with wings spread like hands fan sits in the middle of the bejeweled gold crown. The eye of the peacock sitting on a rosette of flowers is a ruby and the surface of the bird is covered with diamonds. The center of the flower rosette is made of oval-cut emeralds and the petals of diamonds. Both sides of the flower and the peacock are ornamented with symmetrical flowering branches with diamonds. The frame of the crown is enriched with engraved curvy leaves. Sadberk Hanım Museum, 14076-Z. 509.

A pair of Turkish flintlock pistols encased in gold; round barrel chased with foliate decoration.

9.2 x 3.8 cm, 52 cm. The pair of pistols Selim III gave the King George III through Yusuf Agâh Effendi, who was appointed as ambassador to Great Britain. The fact that the grip, the lock, the barrel and the trigger are entirely gold indicates that these muzzle-loaded weapons using black powder were only a piece of jewelry. Royal Collection Trust/Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019, United Kingdom, Inv. RCIN. 62832.

Gold watch, as a rare example of Ottoman jewelry craftsmanship.

Diameter: 3.5 cm. Manufactured by Garabed Babayan and the Kapamadjian Brothers, chief palace goldsmiths during the reign of Abdülhamid II. 18 carats pink gold, classical form, double-lidded, Roman numerals, white enameled dial, seconds hand. The front cover is decorated with a 0.40 carat cabochon-cut ruby in the center, totally surrounded by rose, star and lily designs made with 2.50 carats of diamonds. The lid is inscribed inside with “G. Babayan & Kapamadjian Frères joailliers en chef de S.M.J. le Sultan Constantinople”. Photo: Ankara Antikacılık, 19 April 2020 Auction. Private Col.

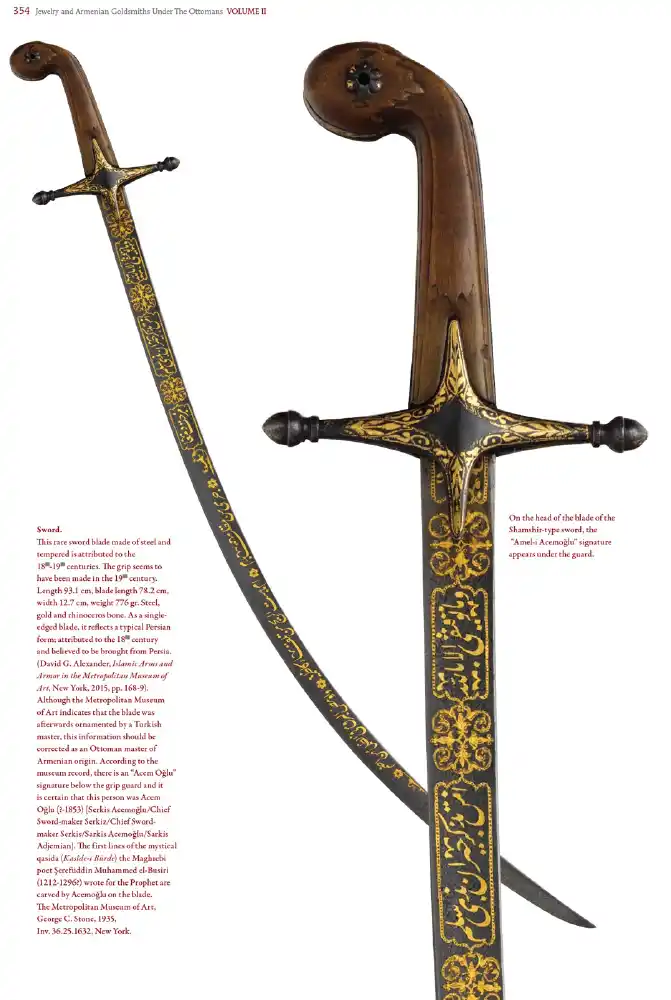

Sword.

This rare sword blade made of steel and tempered is attributed to the 18th-19th centuries. The grip seems to have been made in the 19th century. Length 93.1 cm, blade length 78.2 cm, width 12.7 cm, weight 776 gr. Steel, gold and rhinoceros bone. As a single-edged blade, it reflects a typical Persian form; attributed to the 18th century and believed to be brought from Persia. (David G. Alexander, Islamic Arms and Armor in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2015, pp. 168-9). Although the Metropolitan Museum of Art indicates that the blade was later ornamented by a Turkish master, this information should be corrected to an Ottoman artisan of Armenian descent. According to the museum record, there is an “Acem Oğlu” signature below the grip guard and it is certain that this person was definitely Acem Oğlu (?-1853) [Serkis Acemoğlu/Chief Sword-maker Serkiz/Chief Sword-maker Serkis/Sarkis Acemoğlu/Sarkis Adjemian]. The first lines of the mystical qasida (Kasîde-i Bürde) the Maghrebi poet Şerefüddin Muhammed el-Busiri (1212-1296?) wrote for the Prophet were carved by Acemoğlu on the blade. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, George C. Stone, 1935, Inv. 36.25.1632, New York.

The aigrette on the left.

First half of the 17th century. This tall aigrette is placed in a wooden stem. The gold circular plate with a small upward protrusion and very long feathers, sustain the classical form. Decorated with rubies arranged in an outer circle with diamonds in an inner circle repeating the form of the plate. A very large octagonal emerald with primitive facets is placed at the center of the two circles formed by the jewels.

The aigrette on the right.

Aigrette with Ahmed III’s tughra.

18th century. The base of the aigrette created from wide and long feathers is animated with a circle of rubies and turquoises and inscribed with the tughra of the sultan.

The aigrette on the left.

Late 18th century, early 19th century. This piece exhibits the curvy branches decorated with diamonds, which are characteristic of the aigrettes very popular during the era of changes in the jewelry tastes. A large hexagonal faceted emerald is placed at the center of this aigrette with a gold stem. Photo: Bahadır Taşkın, TSM. 2/334.

The aigrette on the right.

Bejeweled aigrette attached to a kâtibî-type turban. Late 18th century, early 19th century. Height 10 cm, incl. feather 51 cm, width 8 cm. Designed almost as a medallion, in accordance with the Western jewelry taste of the period. … In this aigrette from Selim III’s period, both the stem and the part inserted into the turban are made of gold and it is characterized by the curvy branches decorated with small diamonds. These branches surround the large cabochon cut emerald. Photo: Aramis Kalay,Detail Photo: Bahadır Taşkın, TSM. 2/361, TSM. 13/2122

Adorning weapons with various jewels and precious stones is also an area where jewelers are very competent. The book provides detailed information on this subject, and especially draws attention to the rifle decorated with jewels by Hovhannes Ağa Düzyan for Mahmud I and the bejeweled swords manufactured by Sarkis Acemyan (Acemoğlu), whose works are exhibited in many museums around the world.

The book “Jewelry and Armenian Goldsmiths under the Ottomans” contains 2,500 photographs, documents and visual materials (photographs of jewels, sketches of jewel designs, jeweler seals and signatures.