SAATOLOG

TRACING THE JEWELRY IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

REPORT: SENA ÇAKICI

18 October 2023

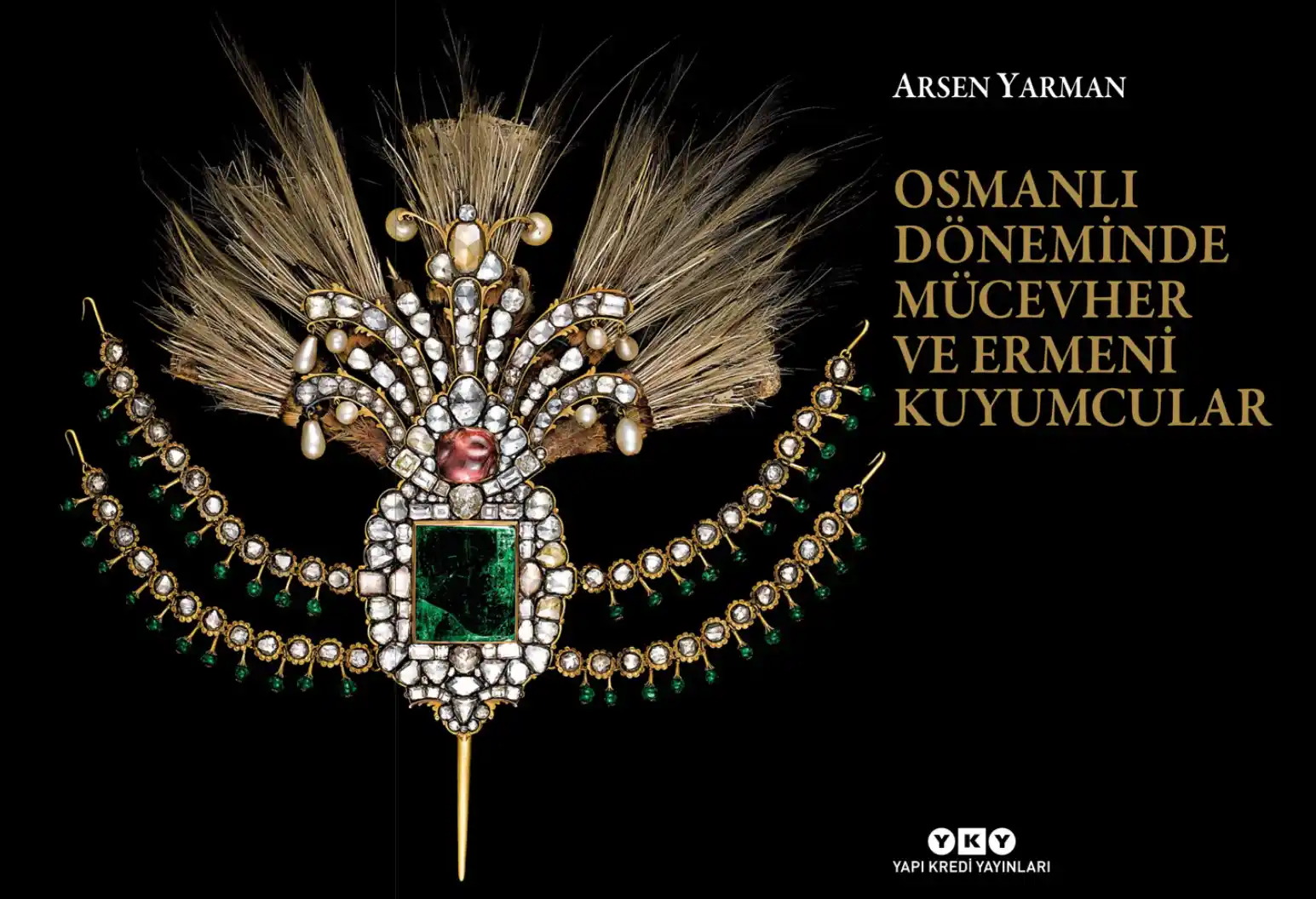

Written by Arsen Yarman and published by Yapı Kredi Publications, Jewelry and Armenian Goldsmiths under the Ottomans traces jewelry through Ottoman archival documents and the memories of Armenian jewelers involved in the craft of jewelry through generations.

ABOUT SAATOLOG

Saatolog (Haute Horology, Life Style, Art, Travel, Wellness) is a magazine and website aimed at passionate individuals in the field of high horology, as well as those interested in various lifestyle areas that may appeal to enthusiasts of high horology. It aims to keep them informed about developments in high horology and other lifestyle areas of interest, provide them with quality content, and contribute to Turkish literature on the subject.

Since 2012, Saatolog has been publishing the “Annual Watch Catalog” a guide containing watches released within the year and brand histories.

Saatolog is a project of Sami Saat. Click here to visit the Saatolog website.

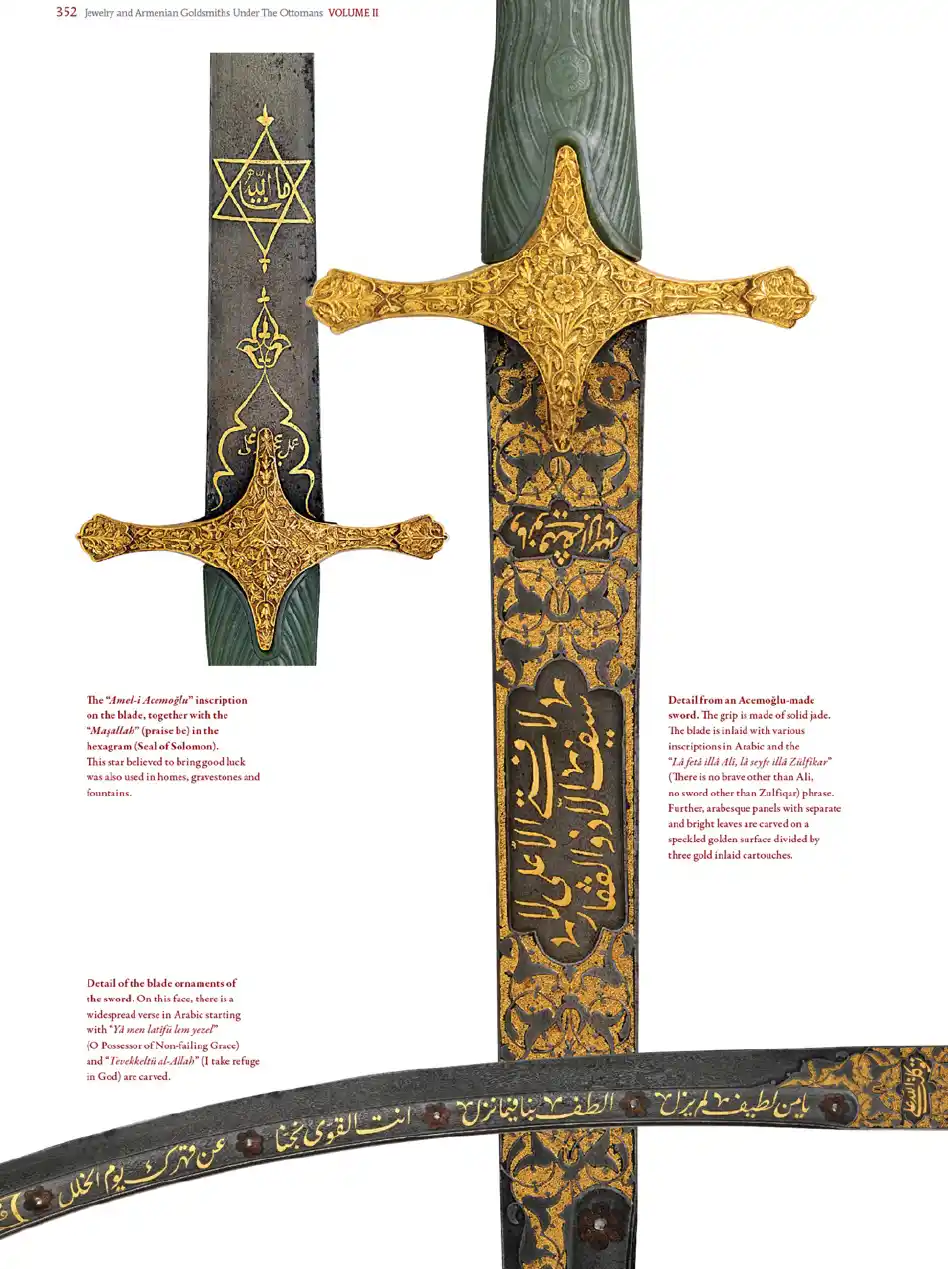

In the preface, you describe that the idea of writing the book came to you from quite a personal place: a watch from your grandfather, a wedding ring from your grandmother, and another family heirloom, a copper lunch box. So I also want to start with these family heirlooms; how did Jewelry and Armenian Goldsmiths under the Ottomans come about?

Whenever I went to the Grand Bazaar, many jewelers would say that they had learned their profession from an Armenian master, and they would also praise the talents and work ethic of the Armenians working in other crafts. In a profession like jewelry, where trust is at the core, a master-apprentice relationship is in a manner of speaking essential. Although Armenians supposedly had the most prominent role in this profession, there have been no serious studies that went beyond hearsay. [Indeed, as Burak Yakın, the Chairman of the Jewelry Exporters’ Association, said, “Although there was a lot of talk about it, there was no data or evidence.”] I wanted to remedy this deficiency with my book, to reveal the quality of Armenian jewelry and to convey their skills to the present.

In the book, you examine Ottoman jewelry making from the perspective of history, beauty, and labor. Sometimes a watch tells the story of times we never knew, just like your grandfather’s watch did. How does the book track memory?

Perhaps the basis for writing the book was these three family heirlooms. Every time I looked at the wedding ring formed as two hands joining together, I would remember the little boy holding his grandmother’s hand. My aunt had the watch and wedding ring and she gave them to me as I was the only male descendant of the family. A friend of mine found the hammer-wrought copper lunch box from 1896 in Tokat and gifted it to me. These were mine and my family’s memories. By making use of Ottoman archives, private archives and interviews with jewelers I tried to deepen this personal memory with the communal memory and knowledge.

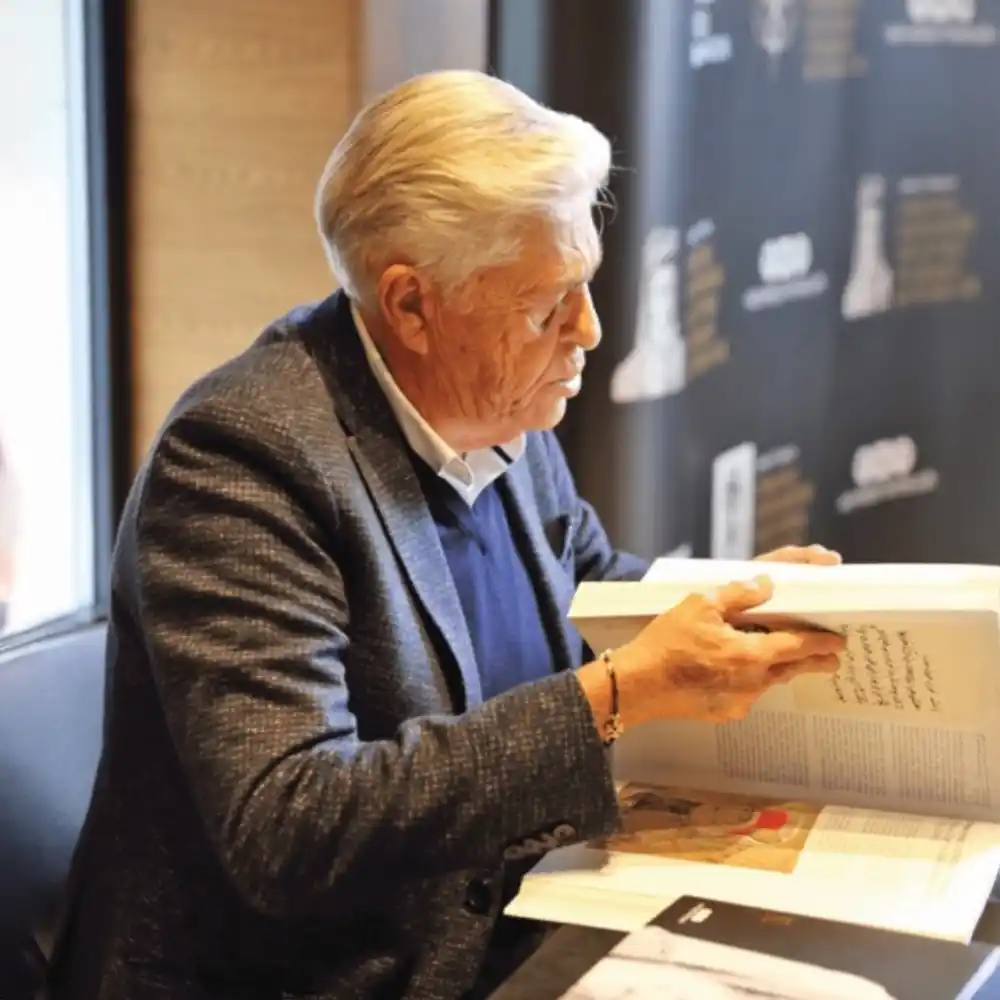

CROSS With Relic

Filigree silver processional cross with relic and ornamented with emeralds, rubies, corals, sapphires and rock crystal. Height 37.5 cm, diameter 23 cm, 1792. This filigree cross with a circular frame ornamented with colored stones of various sizes and turquoises has arms of equal length. The circular glass case in the middle of the cross holds three pieces of relics. There are

Armenian inscriptions in a circular form on the reverse and in a spiral form on the handle. The Armenian inscriptions in the circle on the reverse reads: “Saint John, Apostle Peter, Saint Stephen.

Made by Gevorg of Sufraz.12 Peg Davit-41 [1792]”. The Armenian inscription on the handle reads: “This cross is Sarkis’ memorial to the crosses of the Seat of the Illuminator, 12…” Photo: Hrair Hawk Khatcherian, Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia, Antelias, Lebanon, Inv. 174.

Enameled BOX

Silver, gilded, carved, chased, partially cast, enameled box ornamented with silver filigree,

gold filigree with silver foils, spinel, pearls, coral, turquoise and agate. 30 x 28 x 25 cm, 1787, Adana. This rectangular box in the form of a church was mostly used for keeping the blessed communion bread and sometimes wine. The work of five goldsmiths in Adana is predominantly

decorated with filigree and ornamented with more than 120 precious stones. The three columns with domes on top of the box replicate the style of Armenian churches of the late-Middle Ages. The Armenian inscription around the bottom of the box indicates that it was made during the period of Catholicos Theodoros III [Toros III] Achabahian (1784-1796): “During the time of Theodoros, the Exalted Catholicos of Cilicia, Der Simeon of Balu [Palu] and the Melsaser monks of Adana have brought this church box through their common efforts and given it to be made in this city in 1236 of the Armenian calendar [1787].

Hadji Arkisısdom (?)Buryan. The five goldsmiths made this box together with love and only for the love of Heaven.”

Photo: Hrair Hawk Khatcherian, Klaus E. Göltz, Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia, Antelias, Lebanon.

CROSS ON THE LEFT

Cross belonging to the Very Reverend Father Mgrditch Khrimian. 15 x 8.3 cm. The cross was also used by Patriarch Karekin II Kazandjian (1927-1998; patriarchate term: 1990-1998). Due to the fracture on the body, a similar one was manufactured by Sebuh Maden, Murat Poyraz and Hrant Çizmeciyan and presented to Patriarch Mesrob II Mutafyan on the occasion of his election as patriarch 15 October 1998. The enamel in the center was taken from the original cross.

Photo: Bahadır Taşkın, Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul, Patriarch Hovhannes Golod Col.

CROSS ON THE RIGHT

The cross of the Very Reverend Father Patriarch Shnorhk Kalusdyan. 16 x 8.5 cm; the original cross was not enameled, but Patriarch Mesrob II had an enameled miniature reminiscent of those of Toros Roslin added before he became patriarch.

THE BANAGE

Banage (bishop’s medallion/pendant) with a depiction of Jesus given to Patriarch Shnorhk Kalusdyan when he was blessed as bishop in 1955.

Photo: Bahadır Taşkın, Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul,

Which was the most glorious period of jewellery making since the Ottoman period?

I avoid this comparison because the circumstances, tastes and styles of each period are different. The increase in the goldsmiths’ products and jewellery is related to the precious metal and gemstone trade that increased from the 16th century onwards. From this date on, although the production of valuable objects for churches continued, goldsmiths’ articles and jewelry products were predominantly of a secular nature, besides, jewelry and everyday items diversified. It is possible to say that the Tulip Era was an important turning point in the Ottoman Empire, and that goldsmiths’ products and jewellery were enriched in terms of form and style from the 18th century onwards. However, this does not mean that valuable objects were not produced in earlier centuries or that the jewelry products made for churches were less valuable.

The magnificence of the wreaths and aigrettes embellished with precious stones and the works of Jeweler Asdvadzadur show that the European style was now closely observed, but I do not accept that a piece made in the 16th century is less valuable than those, because that piece reflects the technique, form and aesthetics of its period.

What would you say about the influence of Armenian aesthetics on Ottoman jewellery?

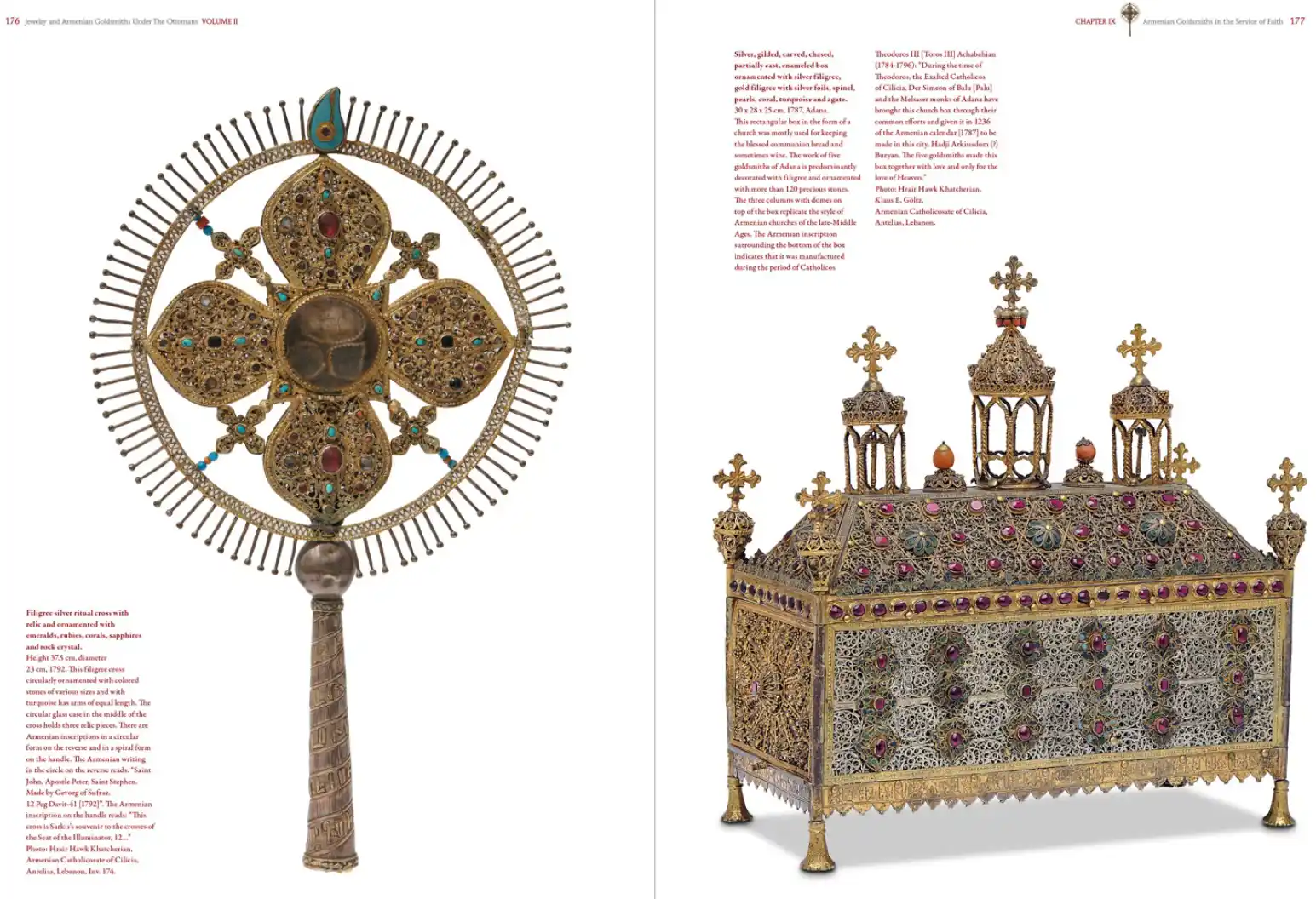

We may speak of a style or form called Armenian aesthetics, but we should not see it as a fixed mold or style. Armenian aesthetics has also changed along with the circumstances of the time and the tastes of the society where it finds itself. For example, it takes different forms in Iran or Russia. In Ethiopia, where there is a strong goldsmith’s tradition, the character of the Armenian jewellers are manifested in a completely different way. Still, I must say that in the most general context, the decorative elements of the Armenian architecture and ornamental stonework as well as figurative details, are discernible in their jewelry, jeweled boxes and cases made of precious metals. We see this clearly in the drawings of table clocks, candlabra, trays, vases, cup holders, frames, tables and the over-decorations in Levon Mazlumyan’s estate or from the gifts produced by Armenians for the 25th enthronement anniversary of Abdülhamid.

Silver Table

An unusual silver table and its overdecoration presumed to have been made at the Ottoman palace. The height of the over-decoration in the drawing is 28 cm, the height of the Ottoman coat of arms is 9 cm. This wonderful drawing, besides combining the details of the contemporary and popular rococo style and the Ottoman coat of arms, technically it represents a competent knowledge of drawing.

Ottoman Coat of Arms

Ottoman coat of arms lead molds. When the dimension of these mold pieces are made to equal the table and over-decoration on the drawing of the Ottoman Coat of arms they match perfectly. Width of the top piece 13 cm, height 9 cm, width of bottom piece 10 cm, height 4 cm.

When you were compiling the book, was there a piece of jewellery that particularly impressed you aesthetically?

Of course, there are countless. Religious objects symbolising ethereal feelings and magnificent aigrettes are very impressive. Hovhannes Düz’s bejewelled decorations on the rifle manufactured for Mahmud I are extraordinary. Abdülhamid II’s jewelery that was sold at an auction in Paris in 1911 is very important as all but a few of them were made in Istanbul. I like the emerald brooch surrounded by diamonds which Mahmud II gifted to Queen Victoria, and the sketch samples of the pieces made by Düzoğlu Hoca Hagop to the Queen of Spain, because they give an idea about the exchanges of diplomatic gifts. The Armenian wedding gold manufactured in the mid-18th century at the Imperial Mint is among the rarer works. The lotus flower shaped brooch sold to Cartier by the antique dealer Kalebdjian Brothers or the silver vase made by Apik Unciyan, which was commissioned by Nigoğos Çizmeciyan for the 25th enthronement anniversary of Abdülhamid II, are impressive. I am also personally very moved by the pendant consisting of a crescent and a cross with four leaves and diamonds set in white gold, as an expression of the religious diversity in the Ottoman Empire.

Pendant with a crescent and a cross.

The crescent edged with blue enamel is white gold and studded with diamonds. Below is the ruby studded bow-shaped middle section, which links the crescent to the diamond studded cross featuring four leaves. This rare necklace alludes to the religious diversity in the Ottoman Empire. It was gifted Yepraksi Pekmezciyan by her mother Güline Pekmezciyan as a wedding gift and it was crafted by Güline Pekmezciyan’s father, who was a goldsmith. The owner of the necklace, Yepraksi Pekmezciyan, was later to change her name to Çakırer upon her marriage. The photograph of the necklace is provided by Vrej-Ümit Çakırer, son of Yepraksi Pekmezciyan. Photo: Bahadır Taşkın

In a way, the life of the artisan comes to life in the jewelry he designed. Can you share an anecdote with us from the stories of the Armenian artisans you have mentioned in the book?

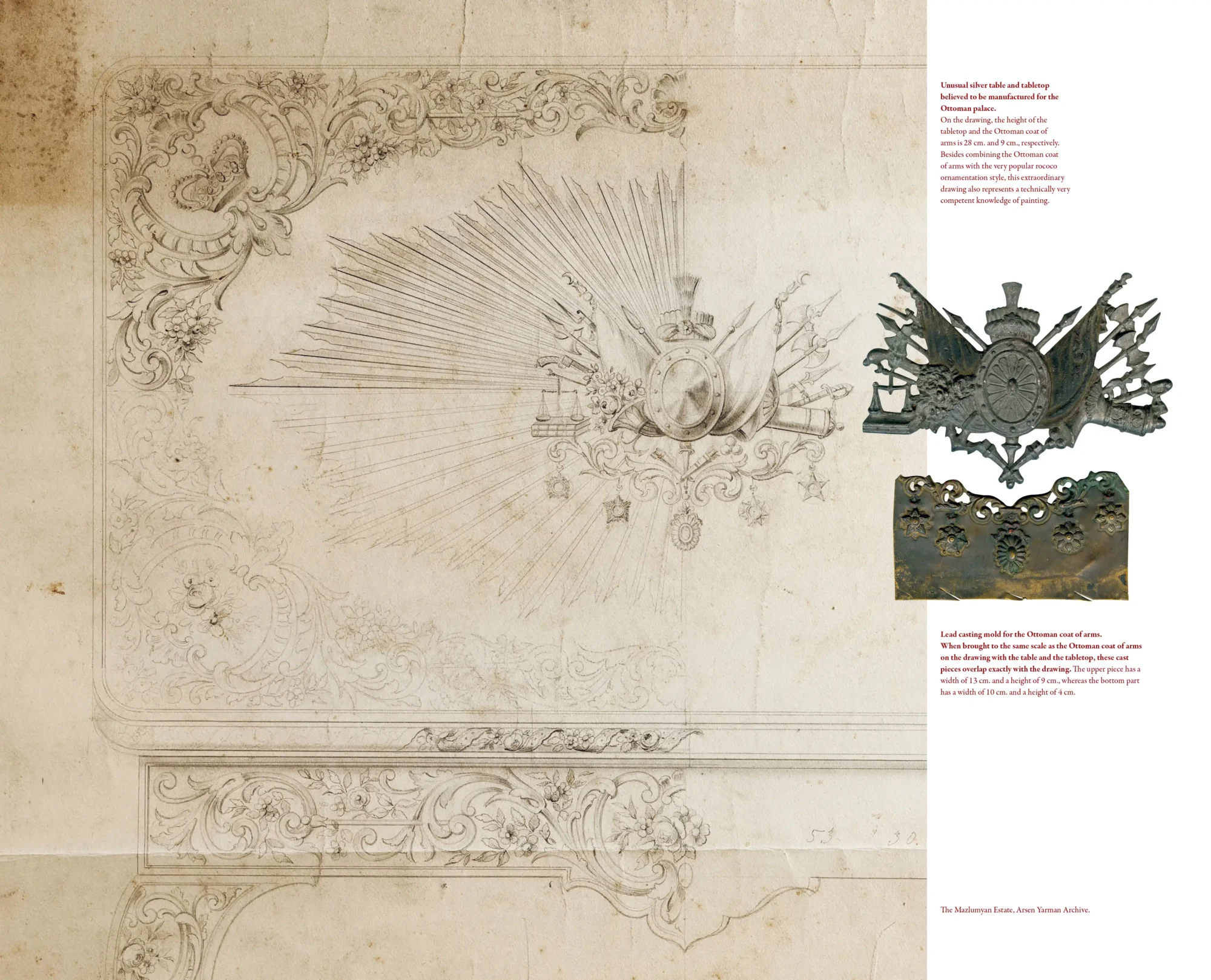

I can tell you the story of how I found the gravestone of Kılıççıbaşı Sarkis Acemoğlu. I had determined that the person who signed his works as “Acemoğlu” and whose swords are kept in museums such as the Metropolitan and Benaki was Kılıççıbaşı Sarkis Acemoğlu, who made swords during the reigns of Abdülhamid I and Mahmud II, and started to look for more detailed information. When I learned that he was buried in an Armenian cemetery in Istanbul, I searched through the entire cemetery and by great luck, I noticed that an upturned gravestone belonged to him. After having identified his name and gravestone, it became easier to find documents in the archive.

DESCRIPTON ON TOP LEFT

The “Amel-i Acemoğlu” inscription on the blade, together with the “Maşallah” (praise be) in the hexagram (Seal of Solomon). This star believed to bring good luck was also used in homes, on gravestones and fountains.

DESCRIPTON ON BOTTOM LEFT

Detail of the saber’s blade ornamentation. On the face, there is an extended verse in Arabic starting with “Yâ men latîfü lem yezel” (O Possessor of Non-failing Grace) and “Tevekkeltü al-Allah” (I take refuge in God) are carved.

DESCRIPTON ON BOTTOM LEFT

Detail from a saber made by Acemoğlu. The grip is made of solid jade. The blade is inlaid with various inscriptions in Arabic and the phrase “Lâ fetâ illâ Alî, lâ seyfe illâ Zülfikar” (There is no brave other than Ali, no saber other than Zulfiqar). The arabesque panels with separate and bright leaves are carved on a speckled golden surface divided by three gold inlaid cartouches.

Saber made by Acemoğlu and signed “Amel-i Acemoğlu”.

The grip is believed to have been made in the second half of the 17th century and the blade in the 19th century. Length 96.5 cm, blade length 83.2 cm, weight 889 gr. Steel, green (nephrite) gold, copper and diamond. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Inv. 36.25.1298, New York.

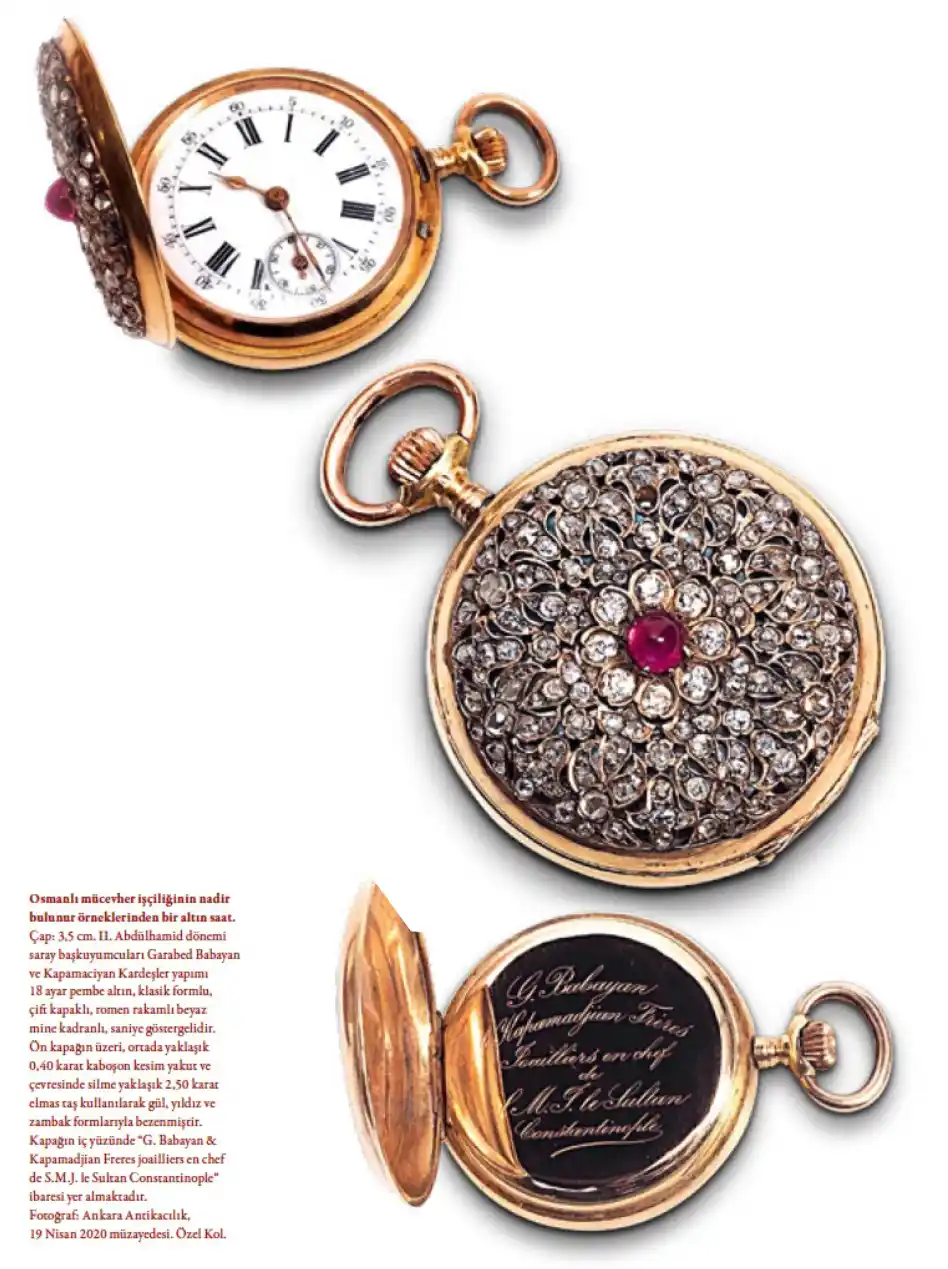

Gold watch, as a rare example of Ottoman jewelry craftsmanship.

Diameter: 3.5 cm. Manufactured by Garabed Babayan and the Kapamadjian Brothers, chief palace goldsmiths during the reign of Abdülhamid II. 18 carat pink gold, classical form, twin-lidded, Roman numerals, white enameled dial, seconds hand. The front lid is decorated with a 0.40 carat cabochon-cut ruby in the center, surrounded by rose, star and lily patterns made by using approximately 2.50 carats of diamonds. The inner face of the lid is inscribed “G. Babayan & Kapamadjian Frères joailliers en chef de S.M.J. le Sultan Constantinople”. Photo: Ankara Antikacılık, 19 April 2020 Auction. Private Col.

How did the tradition of training Armenian jewelers continue? Are there still Armenian jewelers who have been doing this job down through the generations?

Since jewelry is made with precious metals and gemstones, it is closely monitored and based on trust. Therefore, although schools, seminars, courses, etc. are organized, the master-apprentice relationship continues to exist. There are many jewelers who have passed the profession on to the next generation. A good example is the company “Apraham 1882”. It was founded by Serope Büküciyan, who was a purchaser for the palace, on behalf of his son Apraham and it always operated in the Grand Bazaar. The Torosyans, who moved their business in İzmit to Istanbul in the 1920s, were a family that both imported diamonds and closely followed the developments in jewelry all around the world. The Torosyans made outstanding articles with platinum and white gold and at one point they used black coral in particular. Their innovative and abstract designs were in demand in the 1970s and 1980s. Misak Toros, who passed away in 2010, was the fourth generation of the family in the jewelry profession.

In addition to jewellery, the book also includes watches and watchmakers. What do you think about the place of watchmaking in the Ottoman Empire?

Watchmaking is very suitable for the production of luxury goods, and it was also common practice to decorate the watches manufactured for the palace with jewels. Although wall and table clocks come to mind, pocket watches were also an important part of this profession. Watchmaker Şahin’s enameled wall clock from the mid-17th century, Master Mikael of Eyüp’s bronze-decorated domed table clock, the three-layered silver sheep shaped clock signed “Zemberekçioğlu”, the musical clock of Krikor Çuhacıyan, father of composer Dikran Çuhacıyan and apparently the chief watchmaker in the palace during the reign of Abdülmecid, and the wall clock of Yetvart M. Tertzakian are among the first to come to mind. Eminent representatives of watchmaking such as Nasip Cezveciyan, Krikor Arabyan, Tolayan, Pulciyan, Kevork Makulyan, and Garabed Babayan should be mentioned as well. Mazlumyan was also a versatile jeweler and watchmaker.

The “Hamidiye” enameled gold pocket watch manufactured by the Goldsmith J. Tolayan company.

Diameter: 4.8 cm. The case and lid are made of gold, the Ottoman coat of arms on its lid have green, yellow and grey enamelling. The center of a beamed medallion above the Ottoman coat of arms contains a faint tughra supposed to be Abdülhamid II’s. Its main face and seconds face are made of gold and ornamented with floral patterns made of precious stones. The watch is numbered “N 841, 213020” and labeled “Montre Hamidié, Invention Brevetée, Seul Proprietaire, J. Tolayan, Constantinople.” Sotheby’s, 2019.

Jewellery making is a craft that has spread over very wide geographic area like in the distant past. In what way do you think Ottoman jewellery making differs from that of other geographies?

Ottoman jewelers were familiar with Eastern and Western styles from the very early periods. In addition to Byzantine jewelry, they also knew about Iranian jewelry through the artisans brought from Tabriz, and thus created their own synthesis and unique style. From the 18th century onwards, European jewelry was observed closely and the richness of the materials, techniques and styles increased. Armenians, meanwhile, had knowledge of both the market of precious metals and gemstones and the forms and styles of this region thanks to their role in the precious stones trade from Iran and India to Europe which was an important element of long-distance trade from the mid-16th century onwards. They also played an important role in the adaptation of European jewelry to the Ottoman capital.

We know you, not only from this new book, but also from your works on urban history and culture. How do you define the concept “rare”, based on the ideas that come from your continuous studies on cities and cultures?

If I were to answer from a personal perspective, I would say that living as an Armenian in these lands requires one to tolerate experiences that can be considered quite rare. In that sense, I can say that I have lived a “rare” life. In the context of this book, however, I would say that the jewelry and jewelry drawings in the private archives of jewelers are rare.